I recently had the opportunity to interview a friend and former colleague of mine, Bryan Edward Hill. Bryan is a writer and filmmaker who has worked for Esquire, Playboy, and Warner Brothers. Currently, he is writing comics for Top Cow Productions.

Following is a transcript of our conversation, in which we discuss the art of story, the screenwriting process, and navigating the often labyrinthian path to success in the entertainment industry.

me: First, let's talk a little bit what you have been doing recently, and what you have on your plate at the moment.

Bryan: Currently, I'm finishing a mini-series for Top Cow Productions, BROKEN TRINITY: PANDORA'S BOX. I have another comic book, SEVEN DAYS FROM HELL due in October, both co-written with Rob Levin. I have a television project and a feature project in development, but I can't talk about those in detail.

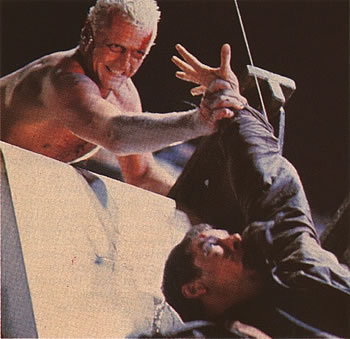

me: Let's talk for a moment about your first produced screenwriting credit, "The Mechanik," starring Dolph Lundgren. How did that opportunity come about?

Bryan: Right. I had written a spec called "ROLAND'S BLUES" and a really great guy, Jay Tobin optioned it from me. Sometime after that it floated past Dolph Lundgren and he read it. Initially, he wanted to direct it, but after a conversation with me via phone (me in NYC him in Spain), he decided he wanted me to write a feature based on his original idea. So I quickly found myself on a Lufthansa flight to Spain and I was working with Dolph every day for about three weeks, writing the screenplay. I came back to NYC with a finished script and then a few months later, Dolph called me to say that he didn't want to use that script at all.

me: What happened with the film after that?

Bryan: Dolph wanted me to come to Bulgaria (where production was to begin) and work on another script. When I arrived there on Thursday, I found out that production needed a shooting draft on the following Monday. So I asked Dolph for a box of Red Bull, he and I worked out a basic story that day and I wrote the draft Friday to Sunday.

me:

me: What was it like working with Dolph at that stage?

Bryan: He's really a brilliant man. Intensely disciplined. This was years ago so I'm sure I looked like a complete neophyte, but he was patient and we got a script done in three days, based on his story. I have to say, for a movie I wrote in 72 hours holed up in a hotel in Sofia, it's not nearly as bad as it should be. I learned something very important then, something about the difference between the "perfect" environment of writing on your own, and writing for a production. I'm sure you know what I'm talking about from EAGLE ONE.

me: Oh, yeah. Not to digress, but an anecdote--we were in Manila for two months before they even cast the leads. Literally twiddling our thumbs and living off of our stipends.

Bryan: Low budget action is all about managing discomfort.

me: Other than the grueling production conditions, did your experience on "The Mechanik" teach you anything enlightening about the business?

Bryan: I learned that when in doubt, trust classic archetypes. With a 72 hour deadline and a page one assignment, I had to leave nuance behind and think about Kurosawa and Leone. I had to remember basic story structure, clear archetypes, because there was a risk of having something unintelligible. Of course, what was shot was nothing close to that level of quality, but without a thorough understanding of basic mythological archetypes, I would have been lost.

me: Are you referring more to Joseph Campell archetypes, or classic film genre archetypes? Or both?

Bryan: Campell for the archetypes, classic films for the execution of those archetypes. Campell teaches you the archetypes and relationships, and all the cinema fused into my brain shows me how those archetypes were executed.

me: Got it. Let's move on to greener pastures now. How did you get the opportunity to write for Top Cow?

Bryan:

Bryan: My good friend and penciler Nelson Blake II started working for Top Cow and he introduced me to Rob Levin, who was editing at the time. He offered me a short story in an anthology book and when he wanted to write full time, we collaborated on our current work. For me, getting writing work has always been about talking to people, showing them my point of view and getting them interested in my work. It's just my opinion, but I think people engage the writer as much as his or her work. It can be a cult of personality, which is both a good and bad thing.

me: Could you elucidate...good and bad in what ways?

Bryan: Good in the sense that if you're a person who can market themselves in conversation, present your point of view, stay "on message" then you can likely move thought the white noise and get opportunities. Bad in the sense that people really don't like engaging work without context. Mailing things to people really gets you nowhere. Submissions without context generally never get engaged.

For instance...

Two young men, could each have brilliant screenplays, but if one of them has a blog with 40 pictures of beautiful women he's taken himself, then that little bit of chuztpah is likely to get him read first. The other writer, with nothing but a brilliant script might languish for years before someone engages the work.

me:

me: Concerning what seems to be the developing relationship between Hollywood and the comic / graphic novel industry: in recent years, Hollywood seems to have developed an insatiable appetite for comic book and graphic novel properties. What is going on here, and is there a way for aspiring or up-and-coming screenwriters to make this relationship work for them?

Bryan: Hollywood prefers to not take the first step. Developing a film from a comic provides a studio the psychological assurance of knowing that someone else first accepted and published the intellectual property. I think it's an attempt to minimize risk. The lesson here for screenwriters is "Don't Let Your Project Look Like Just A Screenplay". Meaning, if you can get an artist to conceptualize your script, then do that. Anything you can do as a writer to turn your script into a fully fledged intellectual property is something you should do.

me: Okay, let's talk about process. Where do your ideas come from?

Bryan: I personally believe that if you don't have a philosophical idea in your story, then you're wasting people's time and money. So usually start with a theme, an idea that I want to explore through a story, something evocative that I think will stay with readers/viewers. To get stimulus, I consume EVERYTHING. Blogs. Newspapers. People watching. I try to live a life where I absorb as much as possible and from what I experience I try and form theses that will be the foundation of good storytelling.

me: What are the major things you consider when formulating the basic plot and structure of a script?

Bryan: The first is making sure that the story is the most important event in the life of the protagonist. Sometimes I'll start thinking through a story and then realize that the most important character arc is actually earlier or later in the life of that character, so I have to alter the story accordingly. Then I have what I call the "Pillars" of my structure. To me, the most important moments are the "Call to Adventure", the "Acceptance of the call" the "Midpoint", the "Darkest Moment" and finally the "Climax." Once those are in place, it's simply a matter of filling in the space between.

me:

me: Do you find screenwriting gurus like Robert McKee and Blake Snyder helpful in that regard?

Bryan: I think any discourse on craft is helpful. Things get "trendy", and right now Blake Snyder is the common language of executives, but I think it's all helpful. The key isn't to cuddle up to one source, but to look for the common things between them. In most of these books you'll see the same narrative moments given different names. If you see something in 3-4 books, then you can have faith that it might be something to incorporate into your craft. Beware thinking any book or approach is a magic bullet, they're not.

Also, what you're doing on your blog is useful. Break down your favorite films and see how the various structural approaches apply to them. You'll never understand something as much as what you love, so use that love and take your favorite work, analyze the hell out of it and understand what makes it work for you. I've probably learned just as much from re-watching TRANSFORMERS: THE ANIMATED MOVIE as I have from reading Christopher Vogler, Campell or Snyder.

me: Me too! That is such a forgotten classic.

Bryan: It's GREAT. It's a textbook in character introduction. Look at how they introduce Megatron, Unicron and Optimus Prime.

me: Yep, it's masterful. Speaking of structure, by the way, George R. R. Martin has said that there are two kinds of writers...those who plan everything out before they begin writing, and those who "cast seeds" and let them grow, in other words, who begin writing and then allow the stories to take on a life of their own. Does your process fit into one or both of these paradigms, and which do you feel is more helpful?

Bryan: I think that through practice, you move from one to the other. If for no other reason than maximizing time, I suggest new writers work from outlines so they don't get lost. The thing is for every scene you write, you discard ten. Those scenes, those moments, they don't vanish. They're still in your head, waiting to take shape in something else. So I think the more stories you tell, the more outlining becomes reflex. It's still happening, but you're not as aware of it so the process feels more organic.

me: Let's talk for a moment about the business. In your experience, what are producers and development executives most looking for in a spec script or series? Are they looking for different qualities than they were, say, five ago?

Bryan:

Bryan: There's no way to ever be certain what an executive is looking for because every studio, every company has different mandates. Obviously, you want your script spell-checked, formatted properly. Bound with the standard brass and all of that. I tend to think that every year there are more screenwriters, so there's just more product out there now than there was five years ago. Software makes it easier to format scripts, more books are trying to make the form accessible so more people are writing scripts.

The fact is no one likes to read work from a new writer. I'll say that again....

...no one likes to read work from a new writer.

But there's a silver lining to that cloud.

me: Which is?

Bryan: There are so many free tools that you can use to market yourself. You can start a blog, start a twitter feed, you can engage people into your point of view. You can write a book of short stories and self-publish it through I-Tunes and draw attention to that. In today's global-digital market, if you're obscure, you're just not interested in being known.

It's almost like the 1940's.

In my opinion, we're in a redux of the age of Mailer and Hemingway and Capote, the age where a writer was a personality and the work. There are so many networking tools available for you to build a "brand", but I think most writers don't consider themselves a brand. They're still thinking in terms of "this is my script, please buy it and give me a career". That's antiquated thinking and it takes all of the power you have as a creative entity and hands it to agents, managers and executives. Why would you do that?

me: Exactly.

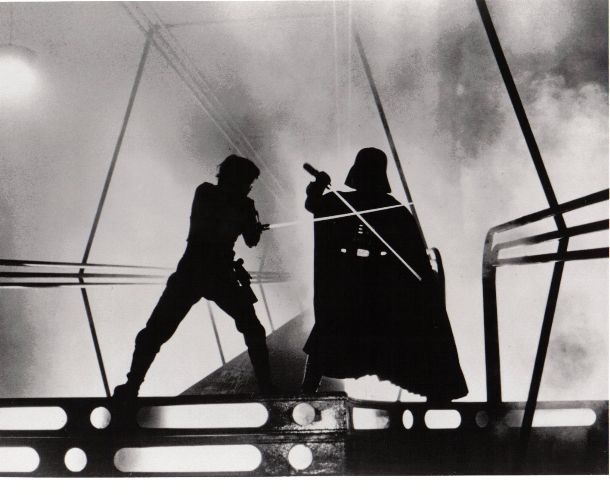

Bryan: The difficult thing is that writers have to study other disciplines too, disciplines that are tied into traditional business. If you're a writer, think of yourself as a company and a brand. Think about your "message". Ask yourself "why would someone want to work with me? What do I bring to the table in specifics". Everyone is a universe of experience and perspective, but most people hide that because they think they need validation to think of themselves differently. At some point, STAR WARS was just some scribbles on a notepad. NIKE was just the dream of a sprinter who wanted better shoes. If you wait for outside validation to believe in your specific talents, then you'll likely never get it. If executives and agents could generate scripts on their own, they would. Clearly they can't, so they still need you. Your job is to remind them of why they need you.

me:

me: That reminds me of James Cameron's experience with THE TERMINATOR...initially almost everyone thought it was a bad idea, including his own agent. He had to go forward tenaciously with complete confidence until someone was finally willing to take a gamble. Which in the end, of course, paid large dividends.

Nevertheless, I think that in this business, we've both come across the occasional gatekeeper who is uneducated in terms of storytelling, and it's often difficult to get them to realize what is and is not a good idea, or what is and is not a good story, etc.. How do you overcome this obstacle?

In other words, to quote what you just said, how do you "remind them of why they need you?"

Bryan:

Bryan: First, I think you need to create an online identity and market the s#$t out of it. I have a blog @

www.bryanedwardhill.com, I have my

@bryanedwardhill twitter feed, and I have a short fiction site @

www.veryshortfiction.com I try to give people plenty of ways to engage my perspective, and I love getting into conversations with readers, other bloggers etc. Second, it's very important to know what you DON'T want to do. Don't be a "one size fits all writer". I'm kinda funny in person, but I don't write comedy. Nothing about my communications says I'll do that. Because I won't. I do sexy, character driven action pieces. If you like those, then you'll like me, if you don't then you won't and I'm fine with that. Third, I don't think you get representation by sending people scripts. Not in this climate. I think you get representation by making waves, in whatever way you can. Find a filmmaker and collaborate on a cool short film. Upload it. There are so many low cost ways you can get exposure. Have a favorite blog? Contact them about writing for them for free. Do a ton of non-fiction posts for them and make contact through them. Agents and managers will find you because they're always looking for the next thing that can make them money.

me: In reading interviews with the great achievers and "peak performers" of the entertainment industry, they nearly always mention the quality of perseverance as critical to success. Will Smith in particular has mentioned the "delusional quality" and supreme faith that all successful people seem to have. What's your feeling about this?

Bryan: At the beginning of any non-traditional endeavor, people are going to doubt you. That's just a fact. No one is going to believe in you more than you believe in yourself, but it's also more than that. By saying, out loud to the world "I want to have an extraordinary life" you're challenging people's basic paradigm. You're saying "I can" when they believe they can't. No one wants to be a thirty-something feeling the glass ceiling in a middle-management job. When we're young we all want to do something irrational. Then adversity comes and most people quit. They justify quitting by calling it "pragmatism", but it's really fear. They quit because they're scared they won't succeed. You've seen that. I've seen it.

The cruelty in the whole thing is that people who quit are never happy. The initial grace and security that comes from doing something standard, something "pragmatic" quickly turns into feelings of deep regret.

This has not been an easy journey for me. I've lost a lot of things, but what I've gained has far outweighed that. I get to walk into the same comic shop where I spent my allowance growing up and see books with my name on the shelf. Here's my best story...

A few years ago I took a meeting on the 20th CENTURY FOX lot. Just a standard "Hey, I'm a screenwriter and I'm new to the business". While walking through the lot, I got passed on the right by a tour bus. I guess they were just tourists visiting a studio lot, scanning for celebrities. That's when I realized that despite the adversity, the first time I walked onto a studio lot, I did it as a professional, not a tourist. I realized that I'd never have to be on that tour bus. For a working class black kid from Saint Louis, that was a victory. At that moment I became intensely grateful for the opportunities I had, and I promised I would never quit. That's the one decision I'm sure I'll never regret.

me:

me: Thanks for that. Are there any other personal or professional qualities that you feel must be cultivated in order to achieve success in the film industry?

Bryan: Humility and gratitude are your rod and your shield. It's really easy to get windswept into a life where you're constantly protecting your ego, but that's self-destructive. Be humble to the craft and remember that experience is your greatest ally. You and I went to NYU with kids that were the children of celebrities, if not that, then they were the princes and princesses of business titans and had limitless resources to assist them. A few of those people have succeeded, but a lot of them have just faded back into their lives. I would tell people not to worry about what other people have and focus on your originality, your point of view, your experience and how that informs your work...and just work harder than everyone else. If one year ago, to this day, someone wrote one page a day...that person could have a novel finished. Or three screenplays. Just from one page a day until now, no more than an hour of their time every day could have created something that could change their life. So the one quality I would tell people to keep in mind is the understanding that your career begins right now. Do something today. Do a little more tomorrow. Eventually you'll get to where you want to go.

me: That reminds me of something Eckhart Tolle said in his book A NEW EARTH: "What the world doesn't tell you--because it doesn't know--is that you cannot

become successful. You can only

be successful." James Cameron said something similar when asked to give advice to those wanting to be directors. He responded: "Be a director. Pick up a camera. Shoot something. No matter how small, no matter how cheesy, no matter whether your friends and your sister star in it. Put your name on it as director. Now you're a director. Everything after that you're just negotiating your budget and your fee. So it's a state of mind is really the point, once you commit yourself to do it."

But to do that, of course, takes an enormous leap of faith, which most people aren't willing to make.

Last question: In the realm of story, either in terms of content or technique, do you feel that there are any frontiers still yet to be explored, i.e., that the industry has yet to make use of?

Bryan: I think youth market content is largely dim to the real experience of being in your teens, or even your early twenties. There's a real lack of understanding there. I also think that studios aren't realizing that we're in "I-Pod" culture, meaning that culturally people are all over the place, taking slices of things and blending traditionally disparate elements into their daily lives. It's time for a new John Hughes, a new Michael Mann, new filmmakers and writers can create things at the speed of culture.

me: Well, hopefully we'll get them. Thanks for your time, Bryan. It's been educational and inspiring.